To what would attribute to the failure of Pearl Harbor? Offering little excuses, Rochefort explains the ones that are typically burdened upon Signal Units: lack of equipment, lack of effectiveness, lack of coordination and a lack of successful cryptoanalysis. These led to failure. The intelligence and communication effort on the island of Oahu suffered for it.

There was a lack of wired communication lines between forward signal sites. Messages were biked or jeeped to respective command buildings. This alone is a failure, especially in light of the attack: the Japanese flanked the island in two successive waves, each massive wave less than an hour apart. The attack itself is well known: the Japanese were to stun the American Navy in the Pacific and hopefully delay retaliation by the US for six months. Radio or telegram is key, in the least, for alerting defensive units.

I would offer that the shape and topology of Oahu should have accounted for this as well. Signal units with proper radio communication should have encircled the island with at least twenty minutes to rally and mount a defense at Ford Island. Having to physically move messages from a site to command, you lose the ability to rally. The wave will already be on top of you before you can respond. Considering that the average Japanese bomber airspeed was around 250mph, you would need sufficient time to signal ahead.

Considering the topology of the island, I would offer what wasn't being done, and fairly similar to what was being done on the Continental Pacific Coast. Close alignment with defensive units, a hub of radio networks, centralized signal command, and close alignment of scout balloons or planes.

Unfortunately, the centralized command at Wahiawa, near the middle of Oahu, was not to be completed until 1942. Most of the radio equipment that could have been deployed in the Pacific was being moved into Europe. Worst of all, the Japanese rightly changed their cryptography on 12/1/41. This proved highly to their advantage. The US would be months away from re-cracking their codes - much less be of any use before the 12/7 attack.

Mobility of stations, not brick and mortar, will always prove invaluable when creating a scheme of operability in a new theater. Camouflage of equipment and periodic cover changes across the face of the island, in coordinated cycles, would have seen a highly integrated and effective network. Extension of the network would have been in the form of scout towers, balloons or planes.

As to equipment, there should have been no excuse. If military equipment is unavailable, the beauty of radio communication is that you don't have to necessarily rely on perfect hardware. Civilian equipment, in the form of existing radio stations, HAM and other readily available types could have, in the least, prevented the situation that the USN saw themselves in prior to the attack.

A logistical issue that Rochefert encountered was relying on crypto-analysis from DC, with very little resources in the field. Of course, there is a reason to keep your best analysis away from a theater of operations, but stations in San Francisco and Los Angeles would have been ideal. If we take Rochefert's mantra to heart, as soon as the code of JN-39 was changed, all efforts should have been made to get some traction on the new codes. From a signal standpoint, a change in codes should have also put a higher alert status in all forward stations.

By the time the Japanese attacked with their first wave (49 bombers, 40 torpedo bombers, 51 dive-bombers and 36 fighters) it was too late. Signal traffic coming at the start of attack does little good when bombs are falling. [The second wave came with 54 bombers, 78 dive-bombers and 36 fighters.]

Strategy would have centralized at Ford Island until Wahiawa was up and running. Five mobile forward sites in Oahu would have called into repeater stations mid-island, pulling in traffic from scouting units. Routing of messages should have gone to both Wahiawa and Ford Island. Forward mobile commands would proven somewhat worthless, so emphasis on scouting units, with a comfortable range of 20 miles out to sea, forms a virtual line of intelligence away from the island (northern islands of the Hawaiian chain prove to hard to defend adequately). This would account for about three scouts to each forward site, or fifteen overall radio units, two repeater stations, and simultaneous command at Wahiawa and Ford Island.

Crypto-analysis should be done on a four hour cycle, with intelligence gatherers collecting data on such a shift, parsing through it and sending off in similar cycles to the mainland for analysis. Gathering would be done repeater stations and at command (adequately done, this would have you looking at twelve trained analysts and a field division office of no more than two captains and a commander).

In such a configuration not only would the attack have been weakened by defensive units on Ford, it could have been repelled. We would assume to that the counter attack by our own air units could have been guided to the correct location of the Japanese, instead of heading to the south as was done.

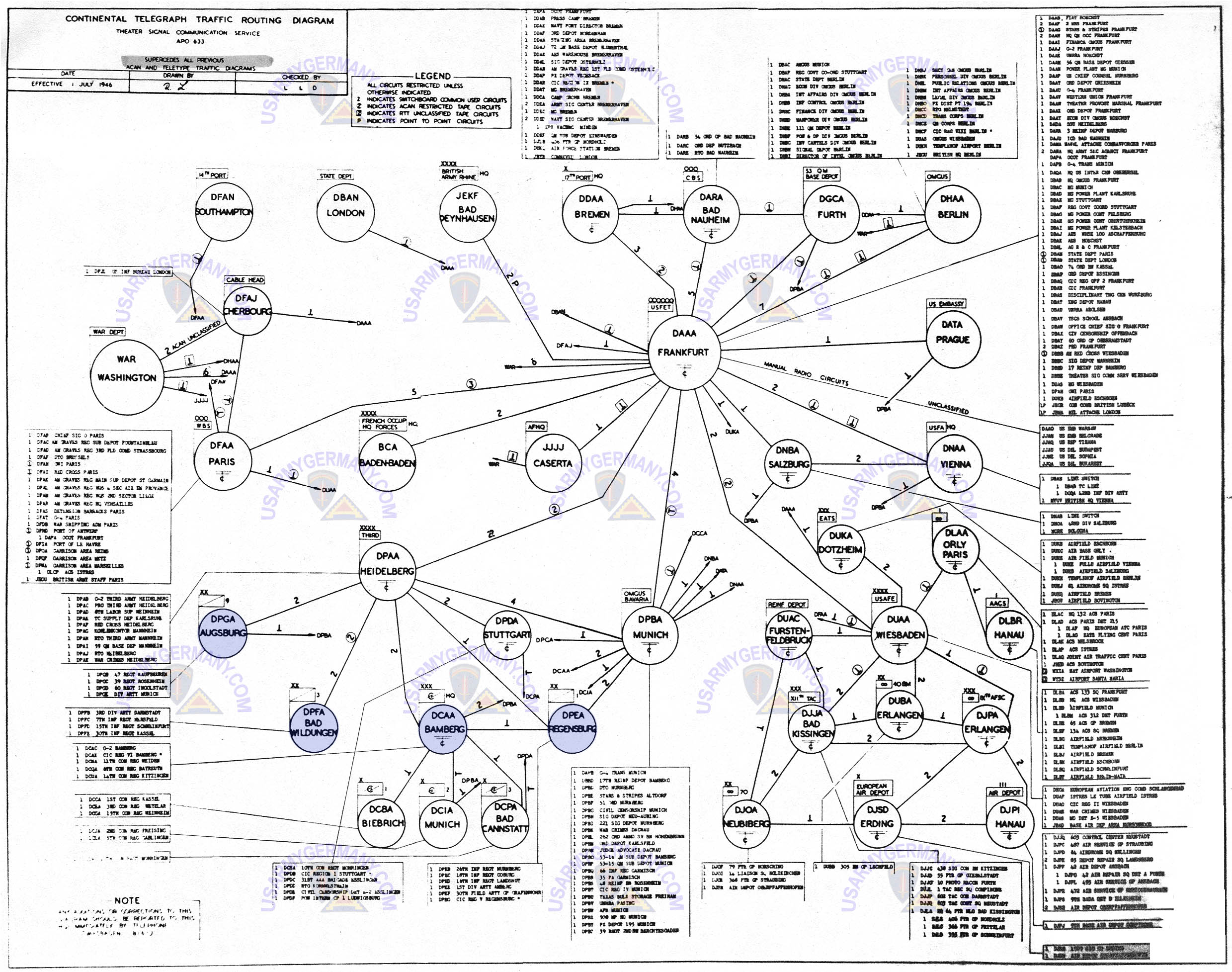

A view of post-war operations in USEUR (US Europe Command) shows the start of a highly integrated network of telegram communications as an example of how such a network should look.

No comments:

Post a Comment