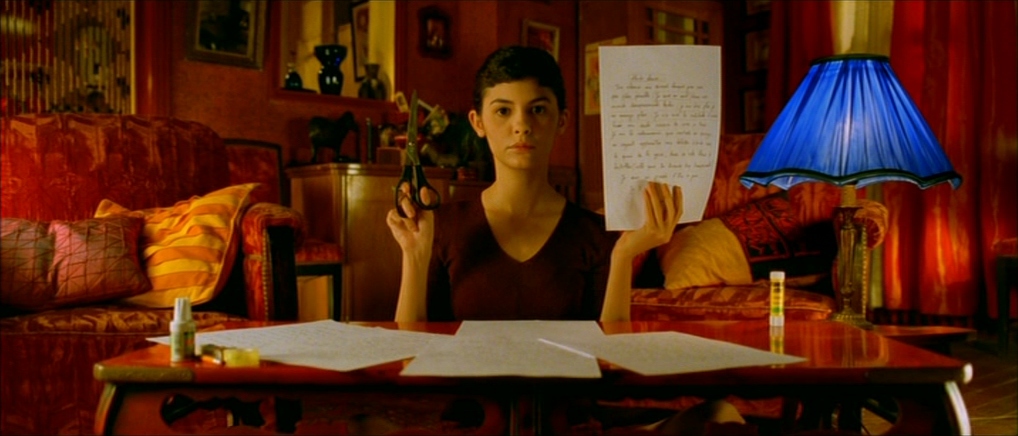

Amélie or Le fabuleux destin d'Amélie Poulain is a 2001 French film from director Jean-Pierre Jeunet and co-written by Guillaume Laurant available for stream on Netflix. The world of Amélie Poulain is full of the richness and vibrancy of a young woman's whimsical nature. A world of rich romance and color, painted by Jeunet and Laurant and brought moreso to life by a young Audrey Tautou.

It's grounding as an original screenplay is wholly apparent as the kinetic energy and overly detailed (OCD like) story begins. It is visual and sensory. It is, at its core, magical realism.

If you reminisce of Gabriel Garcia Marquez, One Hundred Years or Love in the Time of Cholera, you will hear the same frenetic beat. Or visit Laura Esquivel's Like Water for Chocolate, "You must take care to light the matches one at a time. If a powerful emotion should ignite them all at once, they would produce a splendor so dazzling that it would illuminate far beyond what we can normally see; and then a brilliant tunnel would appear before our eyes, revealing the path we forgot the moment we were born, and summoning us to regain the divine origins we had lost. The soul ever longs to return to the place from which it came, leaving the body lifeless.” Joanne Harris' Chocolat is of the same abandoning tone, "I could do with a bit more excess. From now on I'm going to be immoderate - and volatile - I shall enjoy loud music and lurid poetry. I shall be rampant."

If you reminisce of Gabriel Garcia Marquez, One Hundred Years or Love in the Time of Cholera, you will hear the same frenetic beat. Or visit Laura Esquivel's Like Water for Chocolate, "You must take care to light the matches one at a time. If a powerful emotion should ignite them all at once, they would produce a splendor so dazzling that it would illuminate far beyond what we can normally see; and then a brilliant tunnel would appear before our eyes, revealing the path we forgot the moment we were born, and summoning us to regain the divine origins we had lost. The soul ever longs to return to the place from which it came, leaving the body lifeless.” Joanne Harris' Chocolat is of the same abandoning tone, "I could do with a bit more excess. From now on I'm going to be immoderate - and volatile - I shall enjoy loud music and lurid poetry. I shall be rampant."The characteristic elements of magical realism can include the most fantastical elements, the seemingly supernatural, all upon the backdrop and the ground of the real-world. It will sting you with disorienting detail (plenitude as it were). It will key you in to its colors, its smells - the dizzy dancing of life if we lacked the walls to put order to chaos (how sad that world would be). It is Latin American by design, it is Latin American in voice and temper.

Guillame Laurant, the co-writer had his own foundation set by a voracious love of reading as a child, "I read an enormous amount of books,” he says, “obsessively so – almost to an autistic degree, and for me, real life existed in books. I wanted to really live the life of novels; to see and do as much as I possibly could. I left school as early because for me, the idea of going through formal education didn’t make any sense when you could learn so much from experience." The interview is available at Toot La France, Feb 2013. It is shameful that it would lose to Gosford Park for the Academy Award...which is just another exemplary sadness of the awards and the points it misses.

Along with Jeunet, Laurant painted this wondrous world that seems ready to explode from the heart and mind of the young Amélie. Her world is the Sacre Coeur de Montmartre, the Basilica in Montmartre, with its spectacular views of Paris beyond its steps. The Gare de Paris-Est, the Belle Epoque train station once known as the "Strasbourg". The statue adorning it a symbol of the mighty city that bears its name, sculpte by Philippe Joseph Henri Lemaire.

The little Au Marche de lat Butte, open grocer, facing the street with its best fruit forward. The quaint lines of the Lamarck - Caulaincourt Paris Metro. It's irregular shaped lines are pleasing to the eye. And, of course, the Cafe des Deux Moulins, the centerpiece of much of the play, as the characters converge and move from this little cafe. All of it a love letter to the Montmartre district, a center of dozens of painters who used its heights to look across Paris.

Laurant, a self taught writer, had an interesting aside about the role of writing and of cinema and taking the written word to the screen, "I think it's the same problem for literature. Someone who really liked a book, for its atmosphere, for lots of profound reasons to be almost always disappointed by his film adaptation. It's almost a rule. It's rare that we have some surprises in the other direction. A cartoon, a priori, it may pay more, but theoretically, because it has in common with a film to be a story told in pictures. At the same time, from the time when it becomes a movie image, even the frame that is made naturally in the BD has nothing to do with that of a film. One never finds what makes the nature of a comic related to color, design. It will never be quite the same. One has to take a bias by choice or aesthetic or narrative, which can be a successful result after but will anyway else." - translated from Les Nouveux Cinemaphiles, July 2005

Amélie is an example where the media fits the word as the word was designed for the media.

There is no better way to spend an evening with the one you love than with a bit of magical realism on the screen, small tips of limoncello and popcorn with lemon pepper. I've tipped my hat of my wants tonight.

No comments:

Post a Comment