We had risen early. His body had been prepared the night prior. He was stripped of his clothing, but for a loin cloth out of modesty. Interred in a lead casket, the only items that were allowed were reactive rods. One symbolized intrinsic hope, one was regeneration and the last was for humanity. Even after only two generations since we fled to the oceans, the young were already forgetting the last one. That is why I wrote into the Law: that we never forget.

We once inhabited a world with land. We were able to run in fields of grass, under trees. There was life teeming on the planet. Gerald Sivly was the last to see all of this in its last grandeur. I stared into his eyes after he had passed it I felt the heavy pull of loss - loss at the man and loss of his memories. His eyes had seen streets, and cars. He ran among them. He was a child when they ran into the oceans to escape death. It was seventy years ago now. The eyes had lost its light. He was no more.

I held his hands for a time. Even as a child his hands were cut and calloused as humanity pulled together to build what would now be called the System. If it wasn't for him and the 400,000 strong force, there would be little left of the human race and the handful of land species still alive here. We were three million strong now. Three million strong and still petty, still selfish.

That many stout and strong people in the massive structure we had worked on daily, and only a handful to pay tribute. It makes me sick to think on it. The casket topped the rise and my closest family and friends came with him. I had come earlier. I needed time where I can be alone. It was quiet here in the fields. Only larger predators would pass through here, so it was relatively clear. The sharks knew to leave us alone now. But only thanks to Sivly and the strength of the frontiersman. It could have appeared, at the tail of the last century, that the strength of humans was abandoned to technology. But the cosmic dance brought us a storm of comets. Unrelenting, they came bringing fire and water. The world finally tipped and water took the place of the remaining land.

Billions succumbed. Sivly would tear up at that: the waters were filled, for months, with the bodies of the dead and dying. Families tied themselves together. Children, clinging to life, found floating on them. Ultimately they became a part of the sea.

The pallbearers stopped at the foot of the grave. This place was for the distinguished. I turned on the intercom. Anyone inside would be able to hear if they wanted. I had a feeling they would not.

"Gerald Sivly said, of himself, he shouldn't have lived. I paused when he intimated this to me, one quiet night years ago, when the power had blown during the typhoon of '46. I didn't know what to say - I know now, of course. I would have said if it wasn't for you we would not be a federation of peoples, but dissolved into tribes. The great Improvement made forty years ago now. The survey corps. Life. What things would I attribute to you now." I paused when I spoke of him directly. Why would I do that?

"Sivly can be directly attributed to our ability to stay alive. More importantly, we thrived. We have all felt that pang: the too familiar pang we share when events sour, when life makes us dig through hardscrabble to just get by. But we have thrived. Just a few years ago, we formed a library. Our children, in the first time in decades, can feel safe enough to create art: in my lifetime, in Gerald's lifetime.

As we lay him into the soil that once was Earth, where he was born, where he once played," I nodded to them and they put him into the soil. The light dust blew upwards with the weight, clouding the sea around us. "We should remember to keep our heads up, as he taught me. He never flagged. I wouldn't say that he didn't fail, we all do - but he showed, in action, to keep driving forward. He worked until he died." I paused. I didn't do it out of dramatics, we knew nothing of them anymore - I did it because it felt right to pause and think of him again.

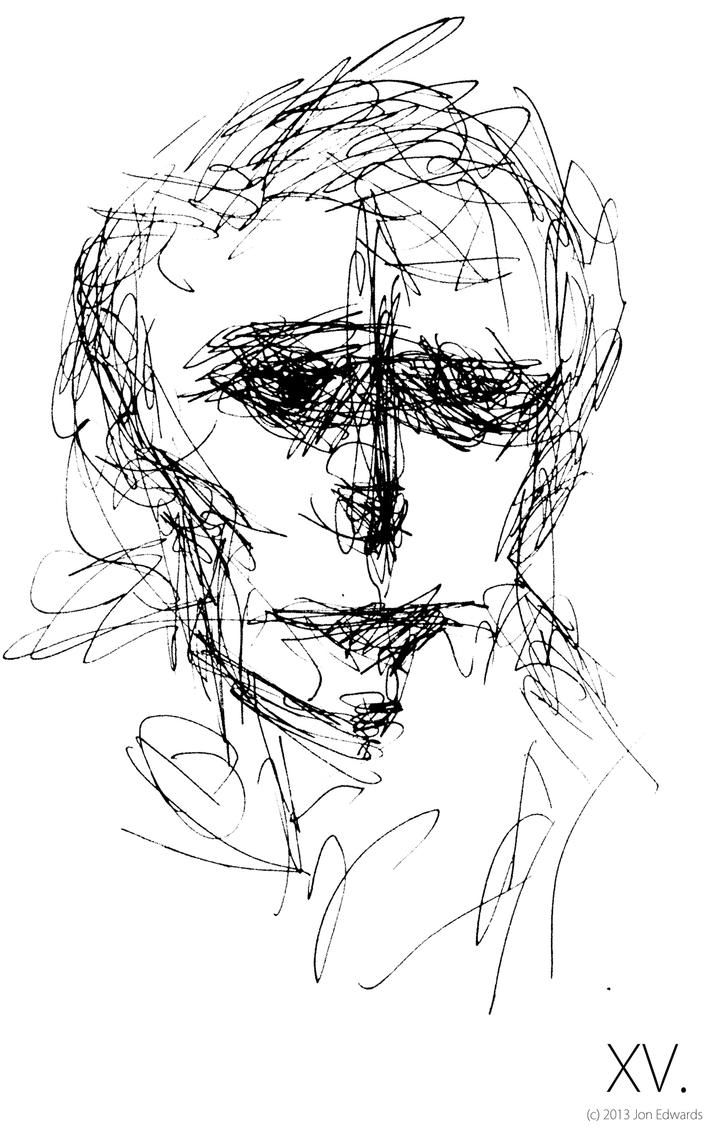

The thousands of times I visited his workshop, but I would remember this singular time: he stood in a shaft of light that had drifted through dozens of feet of clear ocean. The light stayed still long enough to be queer to me. It was as if he was lit by some entity far above us. It was lit for me to remember him, I knew that much. He smiled at me. The light made his ears translucent. His skin was frail even then. But there was a glow. He had animus, he was creating a new tool at his desk. Another tool for us. A tool he remembered or divined. Either way, it was for us. I will not forget this.

"It was an honor to know him. We commit him to the ocean. He will become part of that which he fought so desperately to avoid. But so shall we all."

I stood behind as everyone left. Their figures blurring in the distance, the ever present rise of bubbles from their masks. The dust had settled some time ago. Most of the disruption we caused had already smoothed here. The light was fading. I touched his grave stone and didn't want to leave, like I was a child again.

May my life be even a pale reflection of yours. May I lead these people to a better place. Thank you, father.

I turned and walked quickly, the dwindling dancing light slowly fading in the afternoon, the angular lines of broken cities in the periphery of my vision.

|

| Vitaliy Shushko - io9 Writing Prompt |